![]() Chandra Green, director of Alive and Thrive, holds an “Empowering the Women of Wyandotte County” workshop on trauma and resilience Aug. 14 at Kansas City Kansas Community College’s Mary Ann Flunder Lodge by the Lake. (Zach Bauman/The Beacon)

Chandra Green, director of Alive and Thrive, holds an “Empowering the Women of Wyandotte County” workshop on trauma and resilience Aug. 14 at Kansas City Kansas Community College’s Mary Ann Flunder Lodge by the Lake. (Zach Bauman/The Beacon)

In 2020, one high school lost six students to violence in the span of a few months.

In Wyandotte County, Kansas, a growing coalition of local organizations is working to fight a preventable disease: violence.

According to data from 2019, the most recent available, Wyandotte has the highest homicide rate of any county in Kansas, said Hannah Conner, violence prevention epidemiologist for the Unified Government Public Health Department. It also shows homicide as the most common cause of death for youth ages 1-24 in Wyandotte County.

The Wyandotte County chronic disease dashboard shows homicide as the ninth most common cause of death overall in 2017. Since it disproportionately impacts younger people, it’s ranked fourth on the list of “Causes of Death with the Greatest Years (of) Potential Life Lost” for 2014-16.

The 2019-20 school year was particularly traumatic — Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools lost 23 students, 11 of whom were killed by gun violence.

Conner says the cycle of violence is a public health issue.

“It spreads like any other sort of disease,” she said. “If you’re exposed to trauma or violence, you’re more likely to partake in it later or be exposed again.”

The recent tragedies sparked the start of the Enough is Enough program at Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools.

The program is part of a growing consensus that the community must unite to resolve the complex issues that endanger young people.

“I am seeing agencies come together (asking), ‘What do we do, how do we band together,’ more now than what I’ve seen in the past,” said Chandra Green, director of Alive and Thrive, an organization that seeks to heal the effects of trauma in the community.

“And I think that that is an awesome thing, the collaborations that are starting to happen, the programs that we’re trying to bring into the community, and even the community itself. Our community has a lot of resilience.”

Getting youth involved in violence prevention

A major component of the Enough is Enough program has been to get young people involved with violence prevention.

Last school year, Enough is Enough worked with DEBATE — Kansas City to host a virtual speech contest on youth violence.

In the winning speech, Cherish Heard, a 10th grader at the time, talked about losing friends to violence and suicide.

I believe that that (trauma) has been passed down through generations, and we just have not dealt with it.

CHANDRA GREEN, ALIVE AND THRIVE

“This is a serious and detrimental matter that needs to be resolved in our communities,” Heard said. “Gun violence and suicide is preventable, but it takes effort and courage on our behalf to make sure no more KCKPS students die from this.”

Complementing KCKPS’ efforts, Alive and Thrive takes a trauma-focused approach.

Green says violence in Wyandotte County is rooted in the traumas of the past. She thinks as far back as the underground railroad — the network helping people escape enslavement that had a stop in Quindaro, Kansas — or the battles over Native American land.

“I believe that that (trauma) has been passed down through generations, and we just have not dealt with it,” she said.

Racist housing policies, known as redlining, and a lack of opportunities for employment, education and mental health care also play a role in unresolved trauma, Green said.

But Green thinks healthy elements of the community are already present and just need to be highlighted. Alive and Thrive maintains a resource directory for Wyandotte County and also offers training on recognizing and healing from trauma. Members of Enough is Enough’s youth advisory board took this training.

“We’re tied to each other in so many ways,” Green said. “There are support systems around, and it’s just leveraging the resources to make them stronger.”

Green would like to see the youth advisory board take the lead in determining what young people need, such as carrying out their suggestion of having a mental health event for youths.

“I really would like to see our community make space, more space, for their voice to be heard and to count, and to matter. Because they know what they need,” she said.

Treating violence as a public health issue

Violent deaths can happen in clusters, like when six students from a single school, J.C. Harmon High School, were killed within months in 2020.

Conner, the violence prevention epidemiologist, thinks future clusters might be prevented if someone knows how to step in and break the chain.

One way local public health officials hope to get better at intervention is through a new fatality review board, part of the violence prevention aspect of the Wyandotte County Community Health Improvement Plan for 2018-2023.

The board will examine youth deaths to understand their causes and what attempts for intervention were missed.

It includes representatives of the Health Department, law enforcement, multiple hospitals, child services, courts, judges, district attorneys, public schools and nonprofits.

Conner said she draws inspiration from cities like Baltimore and Oakland, California, that often use a “cure model” to address violence.

The model “treats violence as if it were a communicable disease like tuberculosis. So if somebody is exposed to violence, they will go and speak to them, work with them to provide what they might need,” Conner said.

Conner only focuses part time on violence prevention while she spends the rest of her working hours battling the COVID-19 pandemic. The Health Department is planning to hire another full-time staff member to work on violence prevention, starting in the fall.

“I would love to focus all of my time on violence prevention,” Conner said. “When COVID was down in, like, April and May, I was able to spend a lot of time learning about our initiatives and reading literature and finding out what’s going on in other cities.”

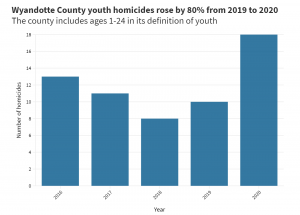

As the pandemic divided Conner’s attention, it also disrupted support systems and added stress to people’s lives. COVID-19 possibly contributed to a spike in youth homicides in 2020, Conner said, though it’s impossible to prove.

Committing to helping youths succeed

Adrion Roberson says the impact of violence on youth in Kansas City, Kansas, is clear.

“It is traumatizing and demoralizing,” he said. “But the challenge is, it’s being normalized — you know what I’m saying? — like it’s just a part of who we are. … It’s not who we are.”

Roberson, who said the best way to describe him is “community servant,” has worked with young people as a coach, pastor and founder of KC United, a youth after-school and summer program.

He said he has seen the detrimental effects of violence and apathy, but also the transformative power of what he calls the “two cuss words in the hood: commitment and time.”

Roberson said he sometimes works with teens who are disrespectful of authority and aggressive toward younger kids because they are imitating what they see at home. But it’s still possible to influence those teens “when you show them something different,” he said.

“There’s a plethora of stories out there of kids and families who have been changed,” Roberson added, explaining his Christian faith is a central component to his work because it goes to the heart. “We just publicize a lot of the negative.”

Conner said approaches to violence prevention should take into account not only known risk factors but also protective factors, such as praise and recognition, constructive activities, stable housing and income, healthy family dynamics, school attendance, and feeling a sense of belonging.

ThrYve, a comprehensive youth violence prevention program, works with an advisory board of more than 40 partners to address systemic risk factors in the broader community and provide structured activities outside of school time. It closely partners with some Kansas City, Kansas, schools and is involved with the Community Health Improvement Plan.

Another goal of ThrYve is to be available wherever young people might need them. For example, the program’s Revive collaboration offers case management to youth ages 12-24 who are treated at University of Kansas Medical Center for injuries caused by violence.

ThrYve also works with a targeted group of about 120 students to provide them with tutoring, employment prep and help addressing barriers to their life goals.

Jomella Watson-Thompson, a University of Kansas associate professor and director of ThrYve, said she appreciated working with Enough is Enough because the program had been especially good at gathering community input on violence and publicizing the issue.

“We know that our young people matter,” she said. “We want all of our young people to be alive. We want all our young people in our families to succeed. And we know that it takes all of us contributing in the ways that we can to change and improve our conditions and our systems, so that our young people are able to fulfill their full potential.”

Article by:

![]()